作者按:这是一篇由死亡引发的随笔,生命的脆弱让我们不禁怀疑艺术这最为人性的产物难道不也是一样的脆弱。尼采的生命哲学把古希腊悲剧奉为推动生命力量最根本的艺术形式。艺术、策展和美术馆如何能把这种化否定为肯定的悲剧形式纳入到自身的语境中,将艺术的死亡视为其生命的一部分。具体到现代主义的定义,艺术始终在创造着自己的"从零开始",这些作品有一种对时间的无畏,也同时是一种"无知"。在21世纪的美术馆中,现代主义已不是那个无畏前行的先锋派,不断的创造和新生被材料的老化和消弭所取代。这时,策展是否应当正视现代主义作为艺术品——作为物——的死亡,重新审视艺术品作为物的生命。生命因为死亡而成立,艺术的生命也是如此。因此让我们一起思考:美术馆如何将尼采的告诫传递给观众?

作者简介:

顺便感伤,伦敦大学学院艺术史及材料研究大二在读。写作关注现时展览及艺术作品和哲学、文化、科学的交叉领域。目前热衷于对现当代艺术、历史及修复理论的研究和相关话题。

Just days before I embarked

on this rumination on curating loss and displaying death, my flatmate's

friend died of car accident at an intersection on the other side of the

Atlantic, aged 21. The resonant chime of death loomed large as I read

about the decay of modern materials. To try to make such immediate experience

of loss and mortality an object of writing and contemplation itself is,

however, somehow antithetical to its inherent embeddedness in our living

experience. To mediate such experience through art and curation may sound

even more forced and lacking of sincerity. But there is no way out of

this pain except through some mediation. And that is perhaps what Nietzsche

was thinking when he wrote The Birth of Tragedy.

What is an experience of suffering and pain? Could it be somehow an aesthetic experience of beauty or sublime? We need the Apolline as a foil against the real and as a semi-transparent layer to make sense of the real. Similarly, we need a camera to look at even our closest friends in suffering, otherwise it's too much. This is how we regard the pain of others, through a lens that protects us from immediacy and heteronomy in the world. Mediation and the Apolline provides us with a safe imaginary position other than one of suffering; we become autonomous and free so to speak from the suffering that occurs through the very medium of life. We are the manifestation of Apollo, the principium individuationis.

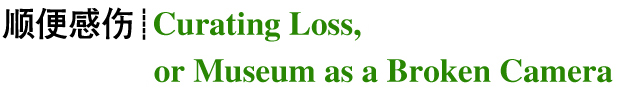

The recent film shown at ICA on the Palsestinian struggle for their land, 5 Broken Cameras, manifests this dialectic movement between Apolline mediation and Dionysiac activism in full force. (Figure 1) Emad Burnat, a Palestinian villager and journalist in Bil'in, joined the non-violent protest against Isreali army through filming with his five broken cameras. "I feel like the camera protects me," he said, "but it's an illusion." The Apolline, the camera position, gives consolation in this struggle between the realm of art and life, the personal and the political. By camera, however, we also posit ourselves in a moment of radical otherness, hovering between heteronomy and autonomy, involved yet detached. The broken cameras are, thus, both debris from that battle between the Apolline and the Dionysiac and a powerful reminder of how the latter will always overpower the former, of how the insertion in the world will always break through the illusions with which we console ourselves. The film, through the lens of five broken cameras, tells the tale of a frustrated reclaim of land and politics and the ultimate tragic death of the cameraman that ends consequently the life of the cameras. The display of loss-the broken cameras, their continually interrupted filming as well as the narrative of loss of political right and physical life-becomes the epitome of how individuals confront political action and think through one's involvement in it.

So that is my pretext, my writing is my broken camera. I would like to think about pain and loss through art, or more precisely, through display, curating and conserving of art, using Nietzsche as the cathartic source of inspiration, so that pain and loss can be both kept at bay for my imagination and less hostile to my own perception and understanding of it.

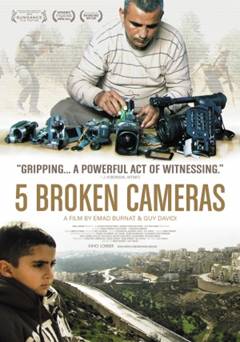

The rather unconventional exhibition on death and skulls at Wellcome Collection opened just the space to think about curation of loss and about creating space to make death ponderable. Walking into the exhibition, you are welcomed by skulls of all kinds, prints, bronze sculptures, and ceramic ware. In the aftermath of a society of spectacle, skull is a sign to be consumed, subsumed, and absorbed. From the works of car crash by Andy Warhol to similar evocation of death in popular culture, and the diamond skull or Natural History by Damien Hirst, death becomes something to be captured, crystallized, spectacularized (Figure 2). Yet the strange resonance of historical voices in Death: A Self-Portrait creates a different dimension that gives the contemplation of mortality an essential temporal lineage. Rather than positing the viewer as the one to be suspended in the moment of 'shock of the new,' in the performantive act of capturing death in the screenprints and installation, the exhibition historicizes the notion and connects us with our ancestors in a diachronic conversation about mortality. In the history of mortality, our fear is not singular but resonant with others'. The shared narrative of death makes us less vulnerable to the thought but rather gives us strength to recognize our own mortality and our fatal identity as a human being. Death and loss is a question to ourselves, of ourselves, for ourselves.

Viewed in close range, this exhibition is also a powerful alternative to the mode of exhibition-driven conservation prevalent in contemporary context. In the narration of loss, object's own mortality becomes highlighted through perhaps the deliberate decision to leave certain aspects of it "unconserved." The painting in 19th century Japan of the floating world inhabited by various skeletons performing circus cabaret and sexual acrobatic has large areas of paint loss which would most possibly de-legitimize its display in any other kind of exhibition space. Walking closer to other panel works also reveals great amount of damage in their frames.

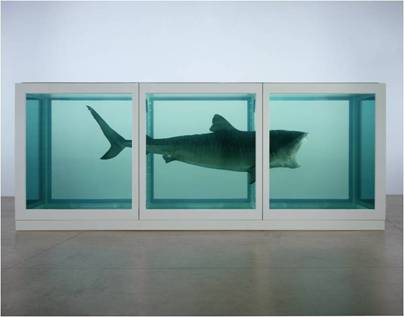

Ruins of works from the past activate and intensify the theme of loss, questioning our desire to keep things pristine. Just like one double-sided portrait in the exhibition that strangely evokes the shadow at the back, our inclination to immortalize ourselves or objects of culture is always underlay by the ghostly shadow of our own mortality. (Figure 3) This shadow lurks at the back, reminding us of the highly surreal setting of almost all other portraiture where the subject sits in a liminal space of indefinite chiaroscuro, a space between life and death. What Roland Barthes said about photography and death, then, is also true for portraiture-every portrait is the future enunciation of the impossible sentence 'I am dead.' In a way, what Surrealists such as De Chirico invokes in their fascination with shadows is a return to the real, mortal world of human being, from which traditional art tried its best to divert our attention. (Figure 4) The German Expressionist films, famous for their horrific and excessive aesthetics of fear, are likewise a strong case against transcendence, where shadow becomes the precise medium through which we contemplate death and brutality. (Figure 5)

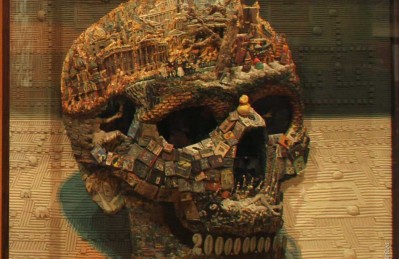

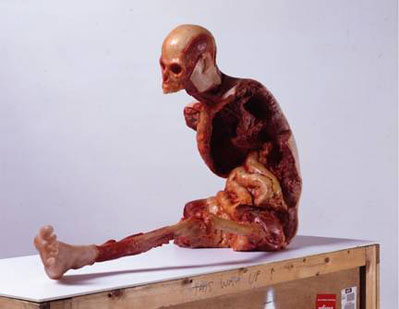

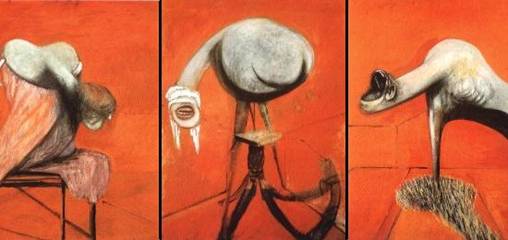

Curating loss, then, is the capacity to create parallax in Homi Bhabha's term, to make shadow an issue and account for it, to call into attention ruins and fragments as an essential experience of one's life and identity. The fragment is not in the avant-gardist sense of visual fragmentation that seeks to shatter subjectivity, but in the ontological sense of the word which considers it as the essential medium of life and subjective experience, and constitutive category in history. In a more literal response to Bhabha's call for a shift in perspective from culture of discovery to culture of destruction, we see a gigantic skull made of plasticine by the Argentine collective group Mondongo. Cultural references are omnipresent; literature classics, fairy tale tradition, abstract expressionist treatment of the material, all serves as a critique on how the dominant economy and cultural mode impact South America. Another example of the metamorphosis between creation and destruction is the contemporary work by John Isaac, 'Are you still mad at me?' Using a wooden box read 'fragile' as support, the visceral wax sculpture of an anatomical figure stands between the immortalizing art and mortal human, eliciting emotional motif in similar thematization of the human body as between life and death, sensitivity and anesthesia, in Francis Bacon's paintings. (Figure 6,7) The box inevitably reminds me of the experience of the installation of art fair in Shanghai where boxes and boxes of fragile works shuffled in and out the space, got damaged, taken away, broken. Not only is the state of art itself, something that we invest so much of our effort to consecrate as immortal, fragile, but the display structure of any exhibition, the institutions that support it, and the art markets that distribute it, epitomized by the 'plinth' of the work, are fragile, too. Death mobilizes our definition of self as well as of art, both a powerful restructuration of the self and a brilliant critique on art institution.

Perhaps, it is time to rethink the mode of institutional practices, especially conservation of modern art, in light of this exhibition. Survival and afterlife is the traditional triumphalist history of art, lurking behind which is the narrative of loss and death. Underlying the performance of miraculous healing of art objects through routine cleaning or radical projects of replication is the notion of conservation as mourning, and the fear that we conservators are no more than a hopeless doctor envisioning the death of all art objects in the indeterminately distant future.

To evoke such melancholy, however, is not to dispense with hope altogether. But rather, similar to how the Wellcome exhibition makes curating of loss an effective reminder of the strength of life and how Nietzschean philosophy posits suffering and pessimism as the ultimate experience of universal will, conservation can be a powerful lens to peer through the modernist myth of eternal newness and enduring ephemerality. Such contradiction is inherent in Modernism, its historical ahistoricism. Thus, the loss and destroyed pieces from artists such as Naum Gabo argues a strong case for the historicization of Modernism as a dialectical movement between radical deconstruction of history and a making of new history. (Figure 8) Instead of the celebration of the reproducible, the forever replenishing abundance of images, Modernism is a site of mourning for the fragility and precariousness of the original in face of the modern world. Conservation and documentation, thus, provide a space for negotiation between history and modernity, death and survival. In place of the miracle-making discourse of modern gallery where objects survive in the aftermath of history and get crystallized in the museum space through the invisible hand of conservator, the new curation mode would rather highlight the agency of conservation as an effort to historicize Modernism and to present it in such way as to throw light on our own conception of mortality. Not only is the narrative of modernity transformed into one that acknowledges its own inherent contradiction and complexity, but the modernist object will acquire a new status as historical performer, acting out its own material decay. The visibility of conservation reanimates the temporal gap closed by the usual museum display, and turns the narrative of forever presence into one of material loss.

The museum space, thus, is the broken camera, signifying our need to capture time in its decisive moment and an individual's impossibility to transcend his/her given time span. We peer through a broken lens in search of the past. The museum-lens, similar to what happens in the film, both acts as a layer that separates the subject from the past and inevitably collapses the boundary through a diachronic re-enactment of decay and loss as a reminder of the subject's own mortality. It is now time that museum adopts a tragic story-telling schema, one that reconciles the Apolline history of illusionistic survival and the Dionysaic dance of immersive loss. The Birth of Tragedy in the museum comes in where curation of loss becomes visible.

Image

List

Figure 1: Poster for 5 Broken Cameras, directed by Emad Brunat, Guy Davidi (2011)

Figure 2: Damien Hirst, 'The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living' (1991). Photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates

Barthel Bruyn the Elder, Portrait of a Man/ A Skull in a Niche (1535-55)

Figure 3: Giorgio De Chirico, Piazza d'Italia (1913)

Figure 4: Film Still from Nosferatu, directed by Murnau (1922)

Figure 5: Mondongo Collective, Skull Series (2009)

Figure 6: John Isaac,‘Are you still mad at me?’(2001)

Figure 7: Francis Bacon, Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion, 1944.

Figure 8: Naum Gabo, Construction in Space, 1937