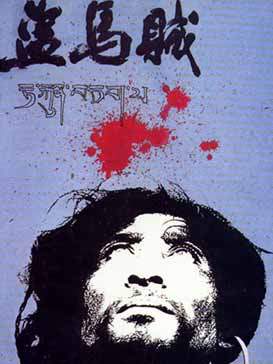

影片海报

导演田壮壮

(翻译/边河)

如果说电影史上美学最繁荣的两个时期是20世纪20年代和20世纪60年代的话,那么很大程度上在这两个黄金时期期间电影已经差不多变成了一门世界语言。一些当代电影评论家认为影像是依赖于语言结构,否认无声电影世界性的主张。但是不可改变的事实是20年代无声电影语言的巩固和精炼符合似乎差不多成为惯例而非例外的多种文化影响下的国际电影文化。

这同样刺激着国际主义,我们看见世界语书写的店标和影响深远的《最后一笑》(1924年)中幕间字幕的虚拟缺席,也让这个时期大多数名家--卓别林、德莱叶、爱森斯坦、弗拉哈迪、格里菲斯、刘别谦、茂瑙、斯坦伯格和施特罗海姆,在其他人中--变成了全球观光一族。“公平交易不是抢劫,”最近Art

Blakey在芝加哥爵士节上就关于他和他不同的伴奏人多年所经历的共同教育时指出说。同样可以这样描述电影史上的那些当国家最大限度对外来思想敞开怀抱的时期。

第二个黄金时期绝大程度上是在新一代导演重新应用20年代的知识和制造其他国际电影文化的努力下出现的。电影五花八门:《广岛之恋》和《哈泰利》、《筋疲力尽》和《放大》、《雪海冰上人》和《华氏451》、《2001:太空漫游》和《玩乐时间》、《轻蔑》和《路易十四的崛起》,事实上都是依据它们所包含的多国元素和情感来进行阐释;就第一时期,从20年代起始--40年代所受到的可能也是唯一的意大利新现实主义影响除外--好莱坞电影制作形式基本上被国外的新发展所颠覆。(目前电影里大部分老一套修辞中一些--像用定格方式结束一部电影--可以直接在这个时期的诸多创新中追根穷底。)

如果采用电影史的循环理论,下一个国际主义黄金时期将是下个世纪的第一个十年。导演田壮壮说过他的《盗马贼》是拍给21世纪的,有人想知道他是否可能已经有了一些这类国际主义想法。这令人称奇的景象的力量来自中国,影片的美国公映安排在这个星期六和下个星期五,在艺术学院的电影中心,为了让直接交流能力达到一定大的范围,超出它地方主义和文化的直接外部标志,而不是提到其地方性和其时代。相关的小角色由对白和情节扮演,配乐和叠印的使用很突出,让人联想起20年代某些电影,尽管它并非一部无声电影:吟唱、打击声和佛教仪式上的钟声以及漂亮的配乐组合在一起成为其文本不可缺少的基本部分。电影在色彩上和对长方形的宽荧幕格式的大胆使用,还有迷人的摄影机运动和不拘一格的剪辑,使电影很容易被拿来与60年代的电影相提并论。

场景设置在遥远荒蛮的西藏,整个演员阵容完全是由非专业演员的西藏居民组成,盗马贼说的是一个名叫Norbu的男人偷庙里的供给被驱逐出宗族,遂意外地成为一名盗马贼。他孤独地与妻子Dolma和他年幼的儿子Tashi住在一起,定期会回到宗族的寺庙去祈祷,似乎是在虔诚地为自己的罪孽悔过,特别是在他的儿子死后。但是过了两个特别严酷的冬天,他的另外一个儿子出生,他发现为了活命家人自己必须再操起偷盗的生计,甚至于还杀死了一只祭神的公羊。在他被宗族的一个可能是其祖母也可能不是的女人告知,他的妻子和孩子是可以回到宗族里去,但是他是“河流的鬼魂,邪恶无比”,他偷其他寺庙的马匹,并用偷来的其中一匹马将自己的家人送回到了宗族。

这些就是大概的剧情,或者差不多尽我所能把他们描述出来,但是它还远没有恰当地描述出这部影片,甚至说叙述;它暗示,例如,Norbu在电影的结尾死掉了,但是到底是不是死了事实上并没有直截了当地表现出来。基本上这是一部关于恶劣地形和严酷气候,关于佛教死亡仪式的电影,从某些方面来讲根本就不是一部叙事电影。至关重要的是,我从情节上注意到电影一直保持着第三方视角。这一视角能让我们得出上面这部分概要,但是并不能让我相信我了解了这部影片或者说任何明确的意义。

田是中国"第五代"导演中的一份子--他们都在文化大革命结束之时进入了北京电影学院,开始接触来自国外的各种各样的电影作品。根据《视与听》的阿兰.史丹布鲁克所说,田和他以前的同学,包括陈凯歌(《黄土地》),黄建新(《黑炮事件》)和吴子牛(《最后一个冬日》)他们“是从戈达尔、安东尼奥尼、特吕弗和法斯宾德那断的奶,尽管现在的这批学生对这些电影导演,或者,的确对之前这些毕业生像陈凯歌和田壮壮的作品不怎么感兴趣,”他们更喜欢研究学习希区柯克和斯皮尔伯格的电影。后者所引至的关注是不可靠的,但是我可以保证几乎没有人能拍出《盗马贼》这样的片子。

北京这批1982年的毕业生的电影还只是刚刚开始在西方得以传播,而且因为某些情况他们在中国还受到限制。一部新出品的中国故事片有100到300个拷贝,而《盗马贼》只有11个,《猎场扎撒》,田以前唯一一部故事片,仅有2个拷贝;他的最新电影《鼓书艺人》的拷贝,很明显可以看出在拍摄上相比以前少了争议性,但是也还是没能被报道。这群导演另外一个明显的特点就是他们的电影都是在西安电影制片厂制作的,当时的负责人是吴天明--和吴贻弓负责的上海制片厂制作的传统守旧的影片形成了鲜明对比。

在发行之前,《盗马贼》就遭受了政府当局两种审查制度的审查。审查的一种是添加,而非删减--在电影第一个画面出现之前闪现了年份“1923年”字样,这样的举动是在特殊时期才会这样做,而不是让影片感觉没有时间概念,但没有时间概念却正是导演的意图。(总之,根据我对佛教和西藏史的粗略了解,电影没有别的什么东西能让其是发生在这个世纪;除了一两个场景中有使用到来复枪,事实上没有出现科技形式来表明它叙述的年代。)审查制度的另外一种形式就是要抹掉电影里的三场不同的"天葬"中第一场要喂给吃腐肉的鸟类中的那些尸体。我们事实上看到这些鸟在被喂肉--它们出现在电影的开始,中间,然后再次出现在结尾处(那时,可能它们正在吃食的就是Norbu)--但是有证原版本更为详细。

田的三部故事片都是有关中国的少数民族文化;《猎场扎撒》是说的内蒙古牧民,而《鼓书艺人》,根据史丹布鲁克所言,是"有关在抵抗战争中从日本人那逃出并定居在中国西南的民间歌手和艺术家。"看来他最初拍摄的两部故事片遇到的一些困难应该是所展示的文化的野蛮所造成的。《猎场扎撒》,据说,很明确是关于屠宰牲口,而今年初《盗马贼》在西方得到初次公映之后--在鹿特丹电影节,也是我第一次看到它--影片出口最初受阻,据了解因为中国政府声称感觉此片会让人对西藏人民生活的自然环境产生误解。

在中共的背景下个人的就一定程度上似乎是反常,很明显盗马贼不能被降格为民族学志研究之用又或者一部旅行记录影片。有人可能想当然地认为如此薄弱的情节被定型为寓言故事是为了突出其独特之处;如果这是电影的目的,我表示怀疑,我搞不懂这一含义。孤立和群体两者之间的不同是电影关注的很明显的一块,但是奇观的优势和佛教的音乐让这一块常常得显得相形见绌,同时让这一不同看上去好像几乎是走题了。(在这方面,《盗马贼》所表现的世界不同于尼古拉斯.雷拍摄爱斯基摩人生活的《雪海冰上人》,尽管在视觉和行为上有相似之处。)影片主要是由一系列短场景组成,配合快速淡出或缓慢淡入迭化,电影让人感觉几乎完全就像奇观一样,似乎更似用音乐词语构成而非描述性的词语。在这个架构中,Norbu人物形象与其说是一个主题,不如说是一件独奏乐器,有时居于合奏音乐篇章之上--孤立中的悲哀,然而从来没有脱离出围绕着的音乐背景。

在再现某些地点、声音和摄影机设置时,音乐感是显而易见的。快如闪电地拍摄一个帐篷的倒塌,这是我们所见Norbu参与到第一次盗马时所弄倒的;Norbu长时间的祈祷和不断俯卧拜倒成就了一个标志性的场景,用了其他几个人物形象恍如催眠式地将摄影机运动和叠印一起使用,就这样含糊地改变了我们对他孤立的感受;Norbu用水壶接住融化的雪缓慢滴落下来的水,这是要带回去给他生病的小孩;复杂结构的场景展现了宗族的西迁,总之,佛教庆典和仪式的描写,其本身形式就很像音乐结构。而且不论田的视觉形式和节奏的高度形式化的特性,这一系列场景从来都没有变得可预知:出乎意料的低视角或倾斜视角,在宽荧幕形式上所有都更为不协调,会突然转到一个完全不同方向的场景过程;或者是在摄影机与一个物体的距离上出现不可预料的移动,让人需要类似的重新适应。

简言之,情节上的不足并没有让人产生缺失的感觉,因为事实上每一个情节都是可以独立存在的。因为在2001年,《盗马贼》所有的一切都是旨在揭示。电影中环境和生态的神秘,都与西藏佛教仪式密不可分,那一点文化的重负,让人联想到安德烈塔可夫斯基的神秘主义,甚至联想到亚历山大杜甫仁科或者谢尔盖帕拉杰诺夫更为民俗的神秘主义,后者更为肖似。可能此片与其他片子最为显著的区别在于景观下的人物形象那种含糊不清的并置;没有任何反人性或者非人性的画面,然而它却让人类与自然处于一种完全不同的关系中。以20年代无声电影特有的大胆和朴素,以60年代折衷电影特有的意识和这一电影过往的发展告诉了我们其中所包含的全球语言部分,《盗马贼》从很多方面来看更像是一部未来电影。

此文于1987年9月18日登载在《芝加哥读者》上。

附英文原文如下:

A Film of

the Future

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

If the two aesthetically richest decades in the history of cinema have been the 1920s and the 1960s, it is in no small part due to the fact that it was during these two golden ages that film came closest to becoming a universal language. Some recent film theorists, arguing that film images are dependent on linguistic structures, have denied the claims for silent film's universality. But the fact remains that the consolidation and purification of silent film language in the 20s coincided with an international film culture where cross-pollination seemed almost the rule rather than the exception.

The same impulse toward internationalism that led to shop signs in Esperanto and a virtual absence of intertitles in the very influential The Last Laugh (1924) also turned most of the giants of this period-Chaplin, Dreyer, Eisenstein, Flaherty, Griffith, Lubitsch, Murnau, Sternberg, and Stroheim, among others-into a race of globe-trotters. "Fair exchange isn't robbery," Art Blakey recently pointed out at the Chicago Jazz Festival, referring to the mutual education that passed between him and his various sidemen over the years. The same could be said of those periods in film history when countries are most open to ideas from abroad.

The second golden age came about largely through the efforts of a new generation of directors to reapply some of the lessons of the 20s and forge another international film culture. Films as diverse as Hiroshima, Mon Amour and Hatari, Breathless and Blow-Up, The Savage Innocents and Fahrenheit 451, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Playtime, Contempt and The Rise of Louis XIV were virtually defined by their multinational elements and sentiments; and for the first time since the 20s--barring perhaps only the impact of Italian neorealism in the 40s-Hollywood styles of filmmaking were fundamentally overturned by new developments from abroad. (Some of the most banal tropes of current movies-such as ending a film with a freeze-frame--can be traced back directly to the innovations of this period.)

If one adopts a cyclical theory of film history, the next golden age of internationalism will be the first decade of the next century. Director Tian Zhuangzhuang has said that he made The Horse Thief for the 21st century, and one wonders if he might have had some of this internationalism in mind. For the power of this breathtaking spectacle from the People's Republic of China, which is receiving its U.S. premiere at the Art Institute's Film Center this Saturday and next Friday, is to a large extent its capacity to communicate directly, beyond the immediate trappings of its regionalism and culture, not to mention its nationality and its period. The relatively small role played by dialogue and story line and the striking uses of composition and superimposition make it evocative of certain films of the 20s, although it is anything but a silent film: the chants, percussion, and bells of Buddhist rituals and the beautiful musical score that incorporates them form an essential part of its texture. And the film's bold uses of color and a rectangular 'Scope format, as well as its mesmerizing camera movements and very eclectic style of editing, make it more readily identifiable with movies made in the 60s.

Set in the remote wilds of Tibet, with a cast consisting entirely of Tibetan nonprofessionals, The Horse Thief concerns a man named Norbu, an occasional horse thief who is eventually expelled from his clan for stealing temple offerings. Living in isolation with his wife Dolma and his little boy Tashi, he periodically returns to the tribe's temple to pray, and appears to be genuinely remorseful about his crime, particularly after his son dies. But after two more harsh winters, and the birth of another son, he finds it necessary to steal again in order to keep his family alive, and even kills a sacred ram. After he is told by an old woman of the clan, who may or may not be his grandmother, that his wife and child can return, but that he is "a river ghost, full of evil," he steals another couple of horses and sends his family back to the clan on one of them.

These are the bare bones of the plot, or as nearly as I've been able to make them out, but they are far from adequate as a description of the film, even as narrative; it is implied, for example, that Norbu dies at the end of the film, but whether in fact he does is not made explicit. Basically a film about the harshness of a terrain and a climate, and the continuity of Buddhist death rituals, this is in certain respects scarcely a narrative film at all. Significantly, it was only during a third viewing of the film that I focused on the plot. That viewing yielded the partial synopsis given above, but didn't convince me that it brought me face to face with what the film was like or about in any definitive sense.

Tian is a member of China's so-called "fifth generation" of filmmakers--those who entered the Beijing Film Academy after the end of the Cultural Revolution and began to have access to a wide range of films from abroad. According to Alan Stanbrook in Sight and Sound, Tian and his former classmates, including Chen Kaige (Yellow Earth), Huang Jianxin (The Black Cannon Incident), and Wu Ziniou (The Last Day of Winter), were "weaned on directors like Godard, Antonioni, Truffaut and Fassbinder, though the current batch of students shows little interest in these filmmakers, or, indeed, in the work of previous graduates like Chen Kaige and Tian Zhuangzhuang," preferring to study the films of Hitchcock and Spielberg. What this latter focus will lead to is uncertain, but I would wager that it could not produce a film remotely like The Horse Thief.

The films of the 1982 graduates of Beijing are only beginning to be circulated in the West, and in certain cases their exposure in China has been limited as well. While anywhere from 100 to 300 prints are usually struck for a new Chinese feature, only 11 were made of The Horse Thief, while a mere two were made of On the Hunting Ground, Tian's only previous feature; print runs of Exile of a Folk Artist, his latest film, which is apparently designed to be less controversial, have not yet been reported. Another identifying trait of this group is that their films are made at the Xi'an film studio, presided over by Wu Tianming--in contrast to the more conservative and traditional films produced at Wu Yigong's Shanghai studio.

Before being released, The Horse Thief suffered two kinds of censorship at the hands of government authorities. One of these was an addition rather than a subtraction--the date "1923," which flashes on the screen before the first image, thus locating the action in a specific period rather than making it more timeless, which was the director's intention. (On the whole, acknowledging my sketchy acquaintance with Buddhism and Tibetan history, there is nothing else in the film that could squarely place it even in this century; apart from the use of rifles in one or two scenes, there are practically no forms of technology present to date it at all.) The other form of censorship was the elimination of corpses from the first of three separate "sky burials" in the film, when human bodies are fed to carrion birds. We do in fact see these birds feeding on flesh-they appear at the beginning of the film, in the middle, and again at the end (when perhaps it is Norbu they are devouring)--but evidently the original version was more explicit.

All three of Tian's features are concerned with minority cultures within China; On the Hunting Ground is set among the herdsmen of Inner Mongolia, and Exile of a Folk Artist, according to Stanbrook, is "about the folk singers and artists who fled from the Japanese during the war of resistance and ended up in south-west China." It would appear that some of the difficulties he has had with his first two features stem from what might be considered the brutality of the cultures shown. On the Hunting Ground, I am told, is fairly explicit about the slaughter of animals, and after The Horse Thief received its first showing in the West early this year--at the Rotterdam Film Festival, where I first encountered it--it was initially held back from export because Chinese authorities reportedly felt it fostered a falsely primitive impression of the nature of Tibetan life.

Personal to a degree which seems anomalous in a Chinese Communist context, The Horse Thief clearly cannot be reduced to an ethnographic study or a travelogue. One might assume that a plot so slender would be shaped like a parable to drive home a particular point; if that is the intention of this film, which I tend to doubt, it is a point that eluded me. The difference between isolation and community is obviously part of what the film is about, but even this concern seems often dwarfed by the dominance of the landscape and the sounds of the Buddhist rituals, which make this difference appear almost irrelevant. (In this respect, it is worlds apart from Nicholas Ray's The Savage Innocents, about Eskimo life, in spite of certain visual and behavioral resemblances.) Composed mainly of short sequences connected to one another by quick fade-outs or slow lap dissolves, the film offers itself almost entirely as spectacle, and as such seems to be structured more on musical terms than on narrative ones; in this framework, Norbu figures less as a theme than as a solo instrument that occasionally rises above the ensemble passages--plaintive in its isolation, yet never divorced from the surrounding musical context.

The musical sensibility is apparent in the recurrence of certain locations, sounds, and camera setups; in the lightning-quick shot of the collapse of a tent, effected by Norbu's accomplice in the first horse theft that we see; in a remarkable sequence devoted to Norbu's extended praying and prostrations, which hypnotically combines camera movements and superimpositions with a use of other human figures that ambiguously alters our sense of his isolation; in the slow drip of water from melting snow that Norbu catches in a jug to bring to his ailing child; in the intricately structured sequence showing the clan's westward migration, as fine a piece of epic poetry as some of the grander collective movements in Ford; and above all, in the depictions of the Buddhist ceremonies and rituals, which are themselves patterned like musical structures. And despite the highly formalized nature of Tian's visual style and rhythm, the flow of a given sequence never becomes predictable: an unexpected low or tilted camera angle, all the more jarring in a 'Scope format, will suddenly veer a scene's progress in a different direction; or an unforeseeable shift in the camera's distance from a subject will bring about a similar reorientation.

In short, the relative paucity of plot is never experienced as an absence because virtually every shot becomes an event in itself. As in 2001, the overall movement of The Horse Thief is toward revelation. The film's environmental and ecological mysticism, while inextricably tied to Tibetan Buddhist ceremonies, has little of the heavy cultural baggage one associates with the mysticism of Andrei Tarkovsky, or even with the more folkloric mysticism of Alexander Dovzhenko or Sergei Paradjanov, which it more closely resembles. Perhaps where it most sharply distinguishes itself from other films is in its ambiguous juxtaposition of human figures with landscapes; without ever proposing an antihumanistic or even nonhumanistic vision, it nevertheless situates the human in a different relationship to nature. Partaking of some of the universal language imparted to us by the silent cinema of the 20s in its compositional boldness and simplicity, and by the eclectic cinema of the 60s in its awareness and development of this cinematic past, The Horse Thief is a film of the future in more ways than one.

Published

on 18 Sep 1987 in Chicago Reader, by jrosenbaum